tales from Constantinople

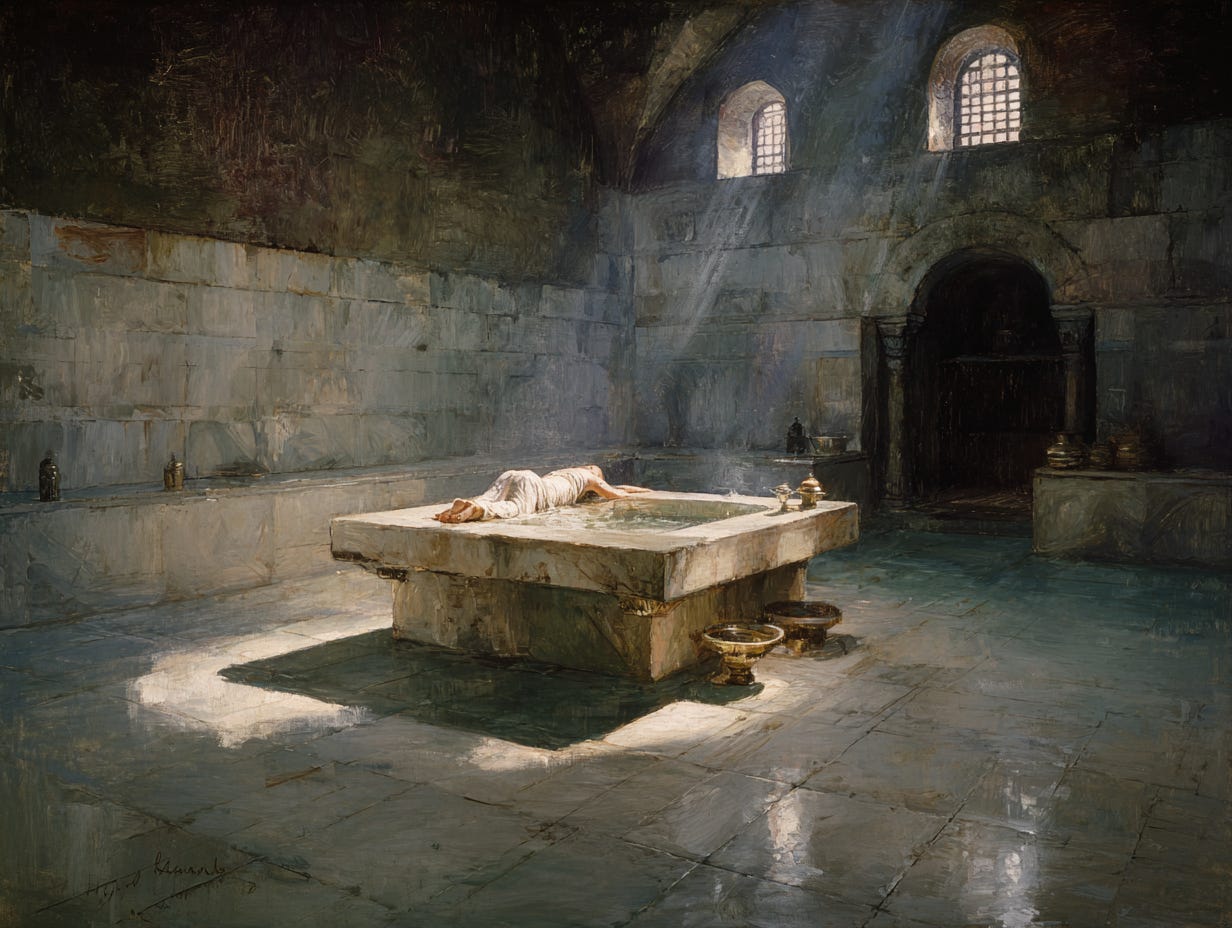

I lie naked on a great slab of marble and prepare to die. The stone table glows with its own heat, even in a room filled with steam. Morning sun slants down from high windows and glints off ornate basins and jugs of beaten copper.

I lay limply and close my eyes. When I am dead I will be washed like this. A final ghusl, a shroud, and eternal rest. Or perhaps, as punishment, I will simply be tossed in a ditch with the pigs.

There was an icon my father showed me once, carried all the way a faraway land where enchanted worms spin silk from the leaves of trees. I remember him telling me in the heart of everything lies a seed of its opposite. Long ago I was told the same by a holy man, a dervish. If he were alive I would have gifted this to him, but now I keep it in his honor.

If my father were alive he would tell me to refuse the Sultan without fear. There is eternal reward, he would have said, in martyrdom. But I was quiet when they stripped me bare, took me away from the other women, brought me to be inspected and questioned by the Valide Hatun, perfumed me and bejeweled me and left me in the Sultan’s bed.

Have you ever laid with a man?

No, I replied. By then I knew the man I once loved had only ever been a boy after all. He had been a laughing, careless youth, with clever playful hands and endless dreams of glory. When the Sultan’s armies came he was among the first to die.

It was a lie, yet it had an inkling of truth. The Sultan could crush my throat with his bare hands and yet in the throes of passion he is at my mercy. With a slight clenching of my thighs I could leave him spent but unsatisfied. And yet I wrap my arms around his back, I place my foot on his thigh, with my hips I draw out his fleeting pleasure till he is breathless. Afterwards I lay, stained by his sweat, as he presses damp, grateful kisses on my shoulder. By morning he is always gone.

I feel no love for this man and yet I cannot find it in myself to deny him this sweetness; I am every inch a woman and weak. But I will not give him a son.

Last night I dreamt of a handsome young boy with flashing eyes, striding like a god through the battered doors of a great church. A haggard, blood-stained soldier is wildly hammering at the floors. The boy asks what he is doing. For the faith, your Excellency! The boy cuts him down with one stroke of his blade, then turns and addresses the rest. Be satisfied with your looting and raping. The buildings of the city belong to me.

The maid gently unravels my hair, letting it fall in limp waves around my shoulders. Softly steaming water is poured on top of my head and flows down in rivers over my skin.

This girl is a slave, but like a child I listen to her murmured commands. She is short and sturdy, with skin the color of wheat chaff, a round face, strange slanted eyes, and black hair damp from endless steam. She turns my head, spreads my legs, bid me to lie down and move my limbs and sit up.

Where does her mind wander as she whips soap into mounds of rose-scented foam, massages it expertly into my skin, polishes every inch of me with fragrant red clay? What does she wish for and fear?

As a woman she knows where to be firm, where gentle. She scrubs my back and legs and arms like she’s scouring a pot. Her fingers slip delicately over my breasts and wrists and thighs, on the bruises and bite marks the Sultan leaves greedily as he feasts. Her hands are as efficient and careful as my mother’s, back when I was small enough to be soaped down in a bucket.

In another, happier world I might have worked alongside her, been her friend. There is honor in what she does, in cleansing and purification. I would massage scented oils onto tired feet, bring blood back into weary limbs, lovingly comb the tangles out of hair. Instead my womb grows a weapon. A weapon that may have my father’s nose, my mother’s eyes. I can feel him stirring as he sleeps and grows stronger.

When she is done she helps me stand. I am rose-red and dizzy from the heat; she somehow is not. She tenderly holds my face and wipes water from around my eyes. Beautiful, she murmurs. You are beautiful.

I smile. Beside her is a dull blade used to scrape away calluses. If I grabbed it and drove it into my stomach, I would bleed out blissfully in this pure place. Soon after she would be put to death. Instead I let her wrap me in a towel and escort me to my bed.

Author’s Note:

I am writing this in Istanbul, over tea and olives and honey. Today the Bosphorus was whipped to a frenzy by strong winds. I could almost see wooden boats fighting their way down it, laden with silk and spices. This city was once Constantinople, the bedrock of Christianity, the seat from which it spread as an institution all over Europe.

Upon the eve of a crucial battle, the Roman Emperor Constantine dreamt of a flaming cross, under which was written the words IN HOC SIGNO VINCES (in this sign thou shalt conquer). Upon victory, he dutifully made Christianity the official religion of the Roman Empire.

Constantine’s conversion was more strategic than it seems on first glance. The Roman faith, lacking any real shared ideology or sense of identity, did not have the power to unite his people. Christianity was still very much a religion of martyrs and underdogs, but it was organized, passionate, and had a strong network throughout the empire. Plus, getting baptized erased all your previous sins; Constantine conveniently chose to get baptized right before he died. One wonders his famous dream was only ever a useful fiction.

Hundreds of years later, the boy who would put an end to the Byzantine Empire once and for all was born to Sultan Murad and one of his concubines, Hüma Hatun. He was educated by the greatest teachers of his time, including Akshamsaddin, a legendary saint and scholar.

I have a fascination with history’s polymaths. Akshamsaddin was a Sunni theologian, poet, and mystic, but also an expert on medicine. He postulated the existence of the microbe in his work Maddat ul-Hayat (The Material of Life) about two centuries prior to Antonie van Leeuwenhoek’s discovery through the microscope.

It is incorrect to assume that diseases appear one by one in humans. Disease infects by spreading from one person to another. This infection occurs through seeds that are so small they cannot be seen but are alive.

Young, audacious, brilliant Mehmed ascended to the throne when he was only twelve years old. He would grow into a ruler of striking contradictions: ruthless yet restrained, a destroyer who wept at destruction (he teared up at the sight of Constantinople in the wake of his army’s pillaging), a conqueror spellbound by beauty. When one of his soldiers started tearing down the great Hagia Sofia cathedral, Mehmed killed him in rage.

Like the mythical Troy, Constantinople was thought to be divinely protected and impenetrable. It was surrounded by water on three sides and the famous Theodosian walls on the fourth. Mehmed was the first to ever take it from the Byzantines and it has remained under Muslim rule ever since.

All these centuries later, Sultan Mehmed is still a hero in Turkey for having dealt such a powerful blow for Islam. There’s a spectacular statue of him flying through an arch on horseback, and locals still frequent his tomb. I saw a guard telling a woman off for spending too much time in it. My friend explained it was okay and common to pray for Mehmed, but you had to be careful not to make it seem like you were praying to him. Which goes to show: even in a secular state, the dominant religion influences culture and norms of decency in ways you’d never think of.

This story imagines Hüma Hatun witnessing the man her son would become. The funny part is, Hüma herself was almost certainly Christian by birth, likely stolen from Serbia before ending up one of Sultan Murad’s concubines.

What little is known of Hüma Hatun reminded me immediately of the figure of Leda in Yeats’s Leda and the Swan: both figures bound to history through an unequal, intimate act whose consequences far outstripped their consent. The title of this story is an homage to that brutal, sensual, farsighted poem.

Leda was raped by Zeus in the form of a swan and consequently gave birth to the half-divine Helen, the legendary beauty who launched a thousand ships in the direction of Troy. There, too, the fall of an impenetrable city and the birth of a new civilization began in the violation of an helpless girl.

The last two lines have always haunted me; in the pattern of great romantic poetry, the meaning is more musical than literal. Did Leda absorb some of the god’s power and prophecy amidst her suffering? In life you can try to avoid pain, or you can accept is as inevitable and aim to gain empathy, insight and humility from it, emerge stronger and free of bitterness.

I feel Istanbul understands such dilemmas. It has been Christian and Muslim, imperial and wounded, conquered and restrained. Its very stones remember that that in the heart of everything lies a seed of its opposite.

"my womb grows a weapon". oh my goodness, that line sent chills. your writing style is otherworldly

Wow! That is some exceptional writing! Great piece of work.